Understanding the PFAS MCLs, Part 1: Drinking Water Standards

By Scott Grieco, Global Principal for PFAS & Emerging Contaminants

The U.S. EPA’s focus on PFAS has continued to forge ahead with almost constant updates. It’s been a rapid pace since the EPA released the pre-publication version of the proposed draft maximum contaminant level (MCL) rule on March 14 – and then posted it in the Federal Register two weeks later on March 29. It feels like there has been a continuous flow of updates and changes – and looking ahead to the range of items EPA is advancing related to PFAS, that may just be an accurate assessment.

But for this series, we’ll focus on the current release: what does the MCL rule say and how will it impact drinking water utilities across the United States?

Between plane rides, speaking engagements and workshops with our clients, I’ve taken some time to summarize my thoughts on this question. And just in case you haven’t had enough PFAS content already, we’ve decided to split this analysis into a three-part series that will discuss six key areas:

1. Drinking water standards (which I’ll discuss here, in Part 1)

2. Best available treatment

3. Initial monitoring requirements

4. Compliance monitoring and notification requirements

5. Right to know requirements

6. Areas where EPA is looking for feedback on the proposed approach

The publication and compliance schedule for the MCL is as follows:

| Date | Activity |

| March 29, 2023 | Publication to Federal Register |

| May 4, 2023 | Public Hearing on Proposed NPDWR |

| May 30, 2023 | End of 60-Day Public Comment Period |

| Late 2023 | Target Publication of Final Rule |

| Sept 2024 | Statutory Deadline to Publish Final Rule |

|

3 years after Publication of Final Rule (an additional 2-year extension may be requested) |

Compliance |

Drinking Water Standards

The proposed drinking water standards include discrete numerical MCL values for PFOA and PFOS at 4.0 ng/L (or ppt) each. The associated Maximum Contaminant Level Goal for each compound is 0, due to the suspected carcinogenicity of PFOA and PFOS.

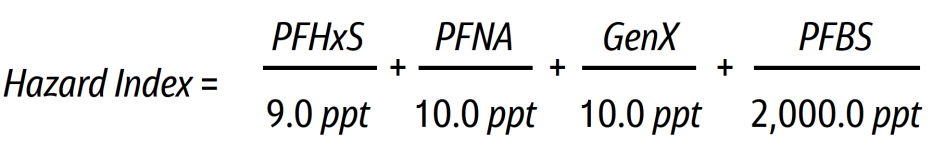

Also incorporated into the standards is a combination calculation called a Hazard Index (HI) that is proposed for four (4) additional PFAS: HFPO-DA (GenX), PFBS, PFHxS, and PFNA. The values for these compounds (10.0, 2000.0, 9.0, and 10.0, respectively) are based on non-cancer health effects. The HI is calculated using the following formula:

If the calculated HI exceeds 1.0, then the MCL standard is exceeded.

OK, those are the numbers, now for some commentary. First, we were all expecting individual MCLs for PFOA and PFOS. However, the HI was not previously hinted. The values represent concentrations at which no adverse health effects are expected to occur over a lifetime of exposure for even the most sensitive populations, with a margin of safety. Two of these we have seen before (PFBS and GenX). They were issued as final Health Advisory Levels (HALs) in June 2022. The other two (PFHxS and PFNA) we have not seen HALs issued under the Safe Drinking Water Act, but numerous toxicological studies exist for these compounds. In fact, there are seven states that have promulgated drinking water values for both PFHxS and PFNA, and many in the same range of single digit to teen values. So, there is support and prior establishment for similar values when we look at State-level agencies (more on this later…).

The concern with these HI values is that they represent three different health endpoints: thyroid (PFHxS and PFBS), developmental (PFNA), and liver (GenX). This approach may raise questions of the additivity of dissimilar health effects.

Back to the states…there are currently 20 states without regulations or guidance values. Obviously these new MCLs could apply, and depending on level of investigation and planning undertaken, understanding the impacts could be a new concern to address.

However, of the 30 states with regulations (draft or final) or guidance values (proposed or issued), the lowest current regulated value for PFOA and PFOS in any state is 5.1 ppt. And with very few exceptions, the values incorporated in the HI calculation are most likely lower than currently published State-level values.

The end result is that every State in the nation will be impacted by these values.

So here is the good news. . . and the bad news:

The good news is that utilities that have implemented treatment in states with existing regulation are ahead of the curve. The capital improvements may already be implemented or underway.

Another piece of good news is that although the resulting Federal MCLs could impact changeout frequency and associated operational costs, in many cases the PFAS in the HI will have more capacity on adsorbent media compared to PFOA. Therefore, if PFOA is dictating changeout, there could be little impact.

The bad news is that it is likely that the HI approach will provide a convenient conduit for EPA to incorporate additional PFAS based on the fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR5) and increasing toxicological health studies available. Therefore, this may be the tip of the drinking water regulatory iceberg for PFAS.

Stay tuned for the next section in this three-part series in which I’ll look at best available treatment and initial monitoring requirements.

About the author

Scott A. Grieco, PhD, PE is a Global Principal and Technology Leader for PFAS and Emerging Contaminants at Jacobs. He is an expert in physical/chemical treatment of emerging contaminants and persistent environmental compounds. Scott has over 30 years of experience in the evaluation, design, and optimization of water treatment systems across the public utility, remediation, and industrial sectors. For the past 10 years, Scott has focused on evaluation and treatment of PFAS. Scott holds a bachelor's in chemical engineering, master's in environmental engineering, and PhD in bioprocess engineering and is a registered Professional Engineer in New York.